I stood at the Partition Wall in Bethlehem two weeks before Easter in 2016.

I wasn’t prepared for how tall it was. It reached to the sky—like the tower of Babylon. It was pure cement—not the steel bars that line the U.S. southern border. Not like the walls that line American prison yards. No. Israel’s Partition Wall is nearly 30 feet high. To approach it felt like approaching a tormented child swinging wildly on the schoolyard. Windmill arms flail and fling and gouge and scratch and punch and lunge and do all they can to fight the bullying ghosts that plague in the present-tense-day.

Gunmen perched in a surveillance tower sat poised to kill any who dare breach the barrier. Electrified wires lined the top of the wall; mimicking the function of razor-wire without the brutal mess of blades and coils. From the Jerusalem side, all Israelis see is concrete—like the sound barriers that line long stretches of the DC beltway where concrete slabs keep sounds of whizzing and whirring car engines from disturbing the suburban lives that encircle our nation’s seat of power. Israel slunk its serpentine partition deep into Palestinian territory; winding around and capturing critical water sources, even as it kept out the sights and sounds from the darker side of the world. Muted cries may rise and mix with vrooming car engines. But, mostly West Bank women’s wailing is never heard. Shrieks rise from Hebron and Ramallah and, and, and… as sons and daughters are stolen off the West Bank streets and thrown into prison by Israeli security. Six years old, 12 years old, 20 years old; they are held indefinitely without charge or trial. According to the testimonies of recently released Palestinian detainees, they are often beaten, humiliated, starved, tortured and even killed. Even so, the women’s sobs are so faint through the Wall that they might be mistaken for birdsong.

The Wall went up in 2002—in the middle of the mayhem of the second Intifada. Intifada means uprising. In 2000, the Second Intifada was likely sparked in response to the failure of the Camp David Summit to reach a final agreement on the Israel/Palestine peace process.

The Palestinian people wanted peace. They could have had it. They waited for it. Then politician Ariel Sharon led 1000 armed police and soldiers to storm into the Al-Aqsa complex of Muslim institutions that sits atop the Temple Mount. A powder keg of violence exploded and burned for five years.

In the middle of the burning, in 2002, Israeli cranes lifted concrete slabs and lowered them atop Palestinian streets, homes and gardens; dividing communities and families. Never, in the history of the land, had Palestinians been so completely cordoned off from Jewish people.

Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi explains in, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, before the Nakba, Palestinian Arabs (both Muslim and Christian) and Jews (mostly Sephardic) had lived on the land since the days of Jesus, who was born in the West Bank’s Bethlehem. The people lived at peace. The Holy land held and nurtured a multiethnic, multi-religious cacophony of peoples. The land was not owned. It was stewarded. It was understood to be God’s land; stewarded my the tenants of the day. And in the days of World War II, 12,000 Palestinian Arabs joined the British Military to fight Nazism alongside 30,000 Jews.

So, the 2002 erection was a profound act of violence.

As I examined the wall in 2016, to my back lay a burned-out village. Left to rot in the wake of partition. People lived here once. They ate here. They danced here. They loved here. Now, even the animals were gone. Burned out cars pushed forward evidence of the life that once was.

A bowl sat on a stripped and rusted car floor. Fabrics lay across the front seat of the burned out car. Windows were blown out. Doors dangled from hinges. I saw the last breaths of the life this car once lived. Likewise, the house that the car sits next to testified about the lives left behind by those removed, jailed or dead. A tree grew through a bombed-out roof. A lone shoe sat in the dust. Tires and uncollected trash lined the dirt as a yellow cat looked for milk—or even water, in a part of the world where water was (and is) cut-off.

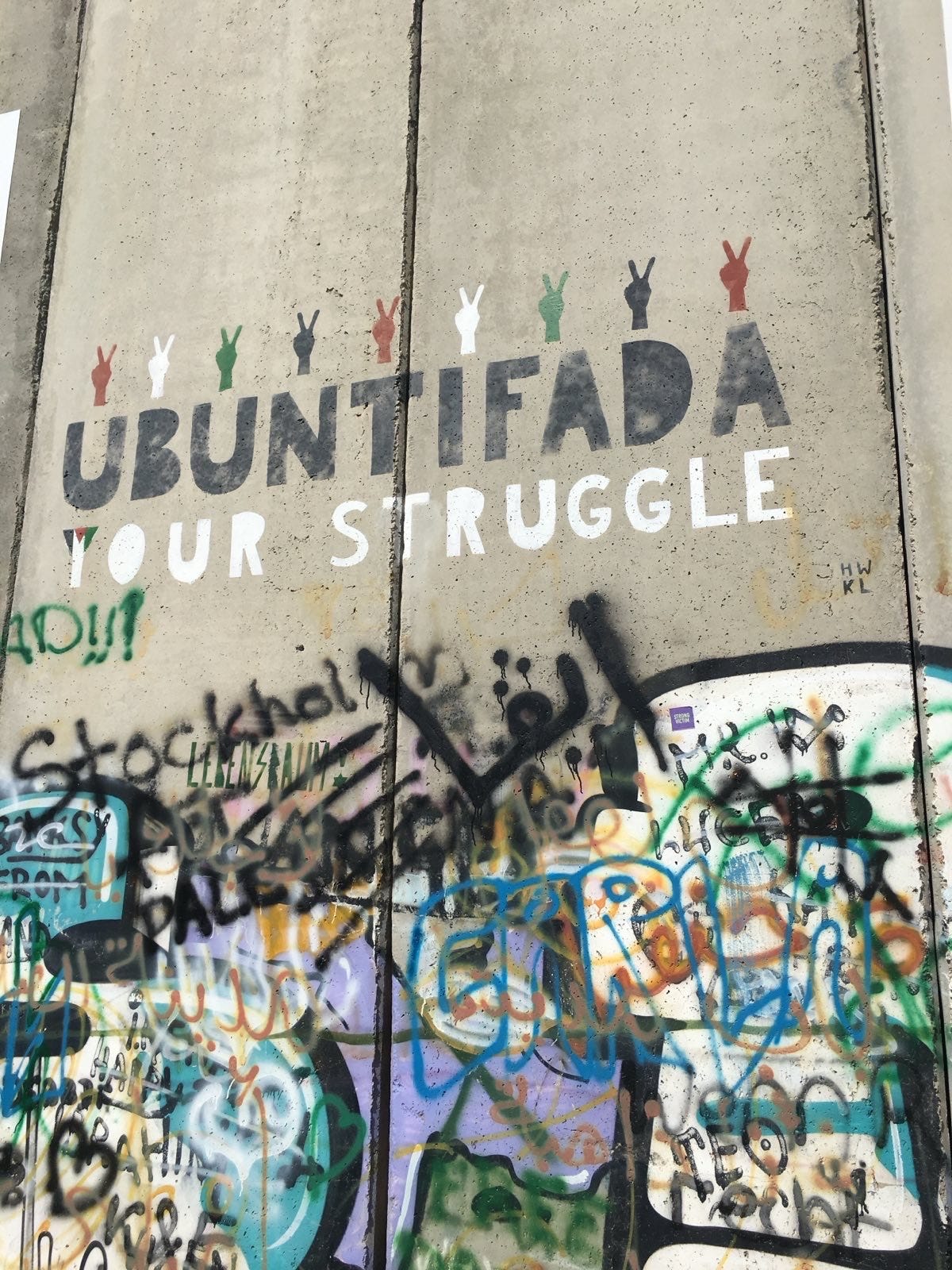

Strewn with graffiti, the partition wall screamed from the West Bank:

“Free Palestine!”

“Build hope, not walls!”

“Remember the women and children!”

“Spirit, break out!” was the caption above two illustrated women kneeling at the base, prying apart a seam in the wall.

Then, I saw it: “Ubuntifada Your Struggle.”

Ubuntifada is a blend of two words: Intifada (uprising) and Ubuntu, the South African philosophy taught by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and President Nelson Mandela at the time of that nation’s emancipation from Apartheid: “I am, because we are.”. The essence of what it means to exist is to be connected. Counter to Rene’ Descartes’s “I think therefore I am,” which illustrates the West’s laser-like focus on the individual as the essence of being, Ubuntu centers the interconnected community. For Tutu and Mandela Ubuntu extended beyond their own families, tribes and state-imposed racialized identities. Rather, Ubuntu, recognized the reality that all South Africans were bound together in one common fate—all equally human and all inextricably connected. The fate of one marked the fate of all. The rights of one marked the rights of all. The identity of one was shaped by the identity of all.

Today, the world watches as Gaza—the open-air concentration camp, the size of Philadelphia—disappears under the weight of 2000 pound bombs.

Netanyahu says he is trying to rescue the hostages, but reports are surfacing that at least three hostages were pulverized by Israeli bombing that hit the apartment buildings where they were held.

Netanyahu says he is trying to end Hamas. But the leaders are not in Gaza and experts agree, each Palestinian death plants the seeds for a larger generation of extremist recruits to take their place.

Netanyahu says he is trying to avoid civilian deaths, but last week Israel evaporated at least 100 Palestinians in one minute when they dropped a 2000 pound bunker busting American bomb on an apartment complex in the densely packed Jabalia refugee camp.

Netanyahu says we are watching a war, but the Israeli death toll has not ticked up since Day 1. It has held at about 1200 since October 7. Two months in, Israel has killed approximately 15,500 Palestinians. Half of them, children. Half. Children.

This is not a war. Experts and an increasing chorus of nations agree: This is genocide.

I stood transfixed.

“Ubuntifada your struggle,” said the wailing flailing Wall. The South African prophet artists placed a new word conjuring united struggle on the cement slab that partitioned the world. Like dynamite, this new word “Ubuntifada” pulverized the spiritual lie of individuality. It unmasked the myth of an independent Israeli future—disconnected from the fate of Palestine and Palestinians.

“No,” says Ubuntifada.

The violence will only end when mothers and fathers and children and grandparents on both sides of the Wall rise up and reach through concrete to touch and listen and weep and laugh and stand together on soil that bears witness to the truth of what happened here. And a common future can be realized when Palestinians and Israelis stand hand in hand and listen to the holy land’s sacred story of common belonging. Then. Flourishing.

Number 10,000

Bombs drop like rain Brown bodies with brown souls cannot dance between the 2000-pound droplets They are too busy picking up little arms Little feet Little ears blow…

Advent in Palestine-Today

On this episode we are joined by Dr. Mitri Raheb, Founder and President of Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem. The most widely published Palestinian theologian to date, Dr. Raheb is the author and editor of 50 books including: Decolonizing Palestine: The Land, The People, The Bible

President and founder of FreedomRoad.us, Lisa Sharon Harper is a writer, podcaster and public theologian. Lisa is author of critically acclaimed book, Fortune: How Race Broke My Family And The World—And How To Repair It All.

Connect

Connect with Lisa: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Threads | Linked In

Connect with Freedom Road: Institute Courses | Patreon | Podcast | Instagram | Threads